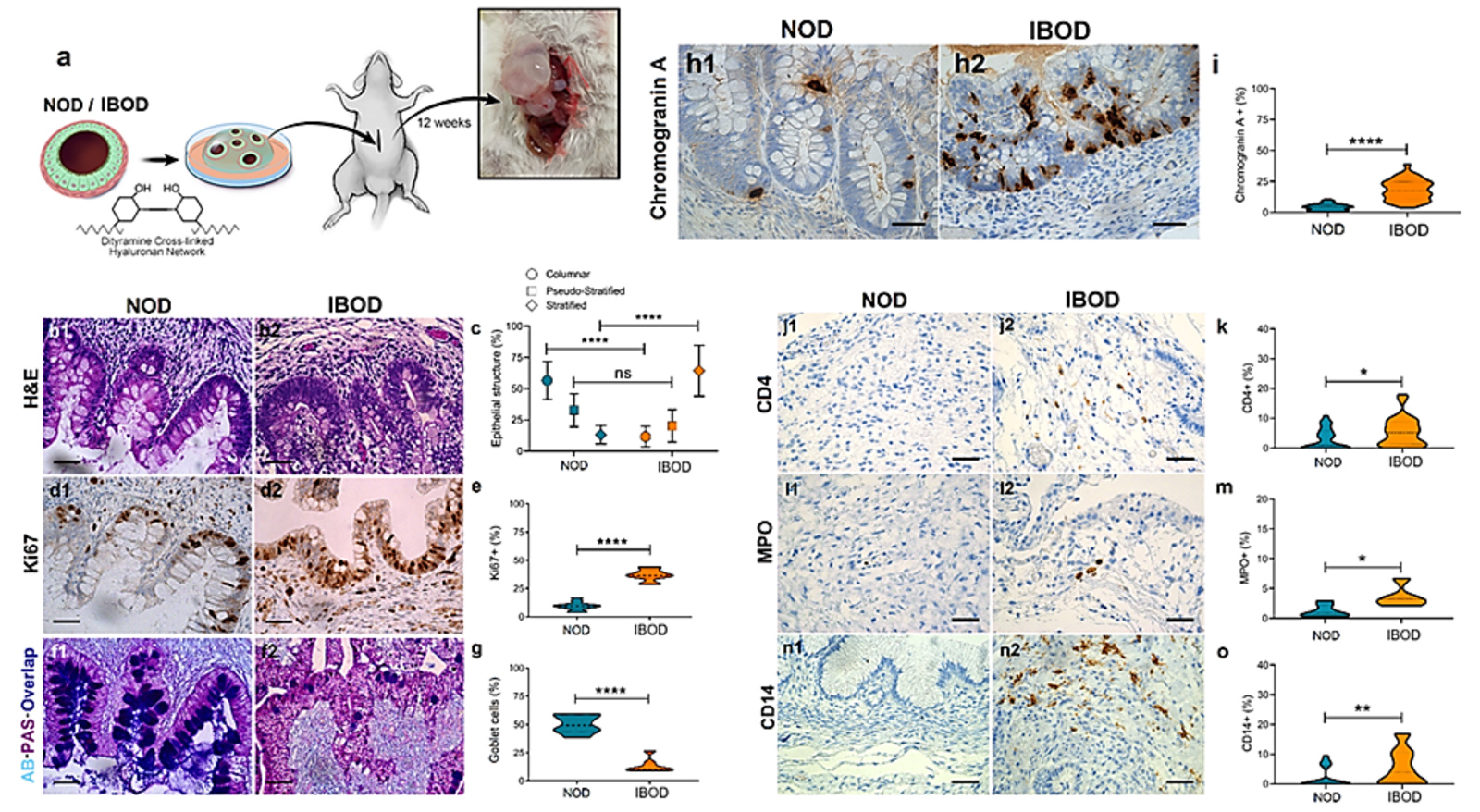

To evaluate whether ODs retain patient-specific phenotypes after transplantation, both IBODs (IBD-derived ODs) and NODs (normal ODs) were embedded in a biocompatible thiol-modified hyaluronic acid (TS-HA) hydrogel and transplanted into the omentum of immunodeficient NSG mice. This in-vivo setting enables long-term tissue integration and provides a stringent test of phenotypic stability and physiological relevance. Sixty days post-engraftment, and histological analysis of retrieved tissues revealed that ODs maintained distinct epithelial and stromal phenotypes that closely aligned with their original source. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining demonstrated that NODs developed organized, columnar epithelial structures typical of healthy mucosa, while IBODs formed colon-like tissues with disorganized, stratified epithelium and shortened crypts—hallmarks of chronic mucosal injury observed in active IBD [1].

Figure 1. IBODs retain disease-specific epithelial, secretory, and immune features after in-vivo transplantation.

(a) Schematic overview of the OD transplantation procedure into the omentum of NSG mice, followed by tissue harvest at 8 weeks. (b) H&E staining shows organized columnar epithelium in NODs and disorganized, stratified epithelium in IBODs. (c) Quantification of epithelial architecture confirms increased pseudo-stratified and stratified epithelium in IBODs. (d1–d2) Ki67 staining reveals restricted basal proliferation in NODs and diffuse epithelial proliferation in IBODs. (e) Ki67+ cell quantification shows significantly elevated proliferation in IBODs. (f1–f2) AB-PAS staining demonstrates preserved goblet cells and mucin secretion in NODs, and goblet cell depletion with reduced acidic mucin in IBODs. (g) Goblet cell count is significantly reduced in IBODs. (h1–h2) IHC for Chromogranin A highlights expanded enteroendocrine cell populations in IBODs. (i) Quantification of Chromogranin A+ cells confirms a significant increase in IBODs. (j1–j2) CD4 staining shows T cell presence in IBODs but not in NODs. (k) CD4+ cell quantification confirms increased infiltration in IBODs. (l1–l2) MPO staining indicates neutrophil enrichment in IBOD stroma. (m) MPO+ cells are significantly increased in IBODs. (n1–n2) CD14 staining reveals monocyte/macrophage accumulation in IBODs. (o) CD14+ cell quantification shows significantly elevated levels in IBODs. Scale bar, 40 μm. n = 3 each. For all comparisons, the unpaired, non-parametric two-sided Mann–Whitney U test was used. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001.

Quantification of epithelial morphology confirmed a significantly higher proportion of non-columnar (stratified and pseudostratified) epithelium in IBODs compared to NODs, consistent with remodeling associated with epithelial wounding and regeneration [2].

Immunohistochemical staining for Ki67, a proliferation marker, showed basal localization in NODs, reflecting the normal proliferative gradient in colonic epithelium. In contrast, IBODs exhibited widespread Ki67 expressions throughout the epithelial compartment, mirroring the hyperproliferative state seen in inflamed IBD tissues [3,4]. This proliferation pattern supports the presence of ongoing epithelial turnover and regeneration driven by chronic inflammation.

Functional mucus production also diverged between models. Alcian blue–periodic acid–Schiff (AB-PAS) staining revealed that NODs retained both acidic and neutral mucin production and a stable goblet cell population. IBODs, however, showed a marked depletion of goblet cells and reduced acidic mucin secretion, closely mimicking the mucus barrier defects observed in IBD patients [5,6]. In addition, IBODs exhibited a significantly higher number and broader distribution of chromogranin A–positive enteroendocrine cells than NODs. These specialized secretory cells are known to be dysregulated in IBD and play a key role in sensing and responding to changes in luminal content [7].

Immunostaining for human immune markers further highlighted the retention of disease-relevant immune activity in IBODs. Compared to NODs, IBODs showed strong expression of CD4 (helper T cells), MPO (neutrophils), and CD14 (monocytes/macrophages) in the stromal compartment. These markers were absent in NODs, confirming the immune-rich, pro-inflammatory state specific to IBD-derived tissue.

Together, these findings demonstrate that CaleoBio’s OD models preserve the in-vivo phenotype of their tissue of origin, including structural organization, cell composition, immune activity, and disease-relevant functional outputs. This stability post-transplantation reinforces the utility of ODs for modeling complex tissue interactions, chronic inflammation, and therapeutic response in both healthy and diseased states.

References

- Pai RK, Jairath V, Gutierrez A, et al. Histological criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease: a joint ECCO and ESP consensus statement. J Crohns Colitis. 2021.

- Wu XR, Lai Y, Chen L, et al. Histological features of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease and their significance in diagnosis and disease assessment. Dig Med Res. 2022.

- Wong NA, Mayer NJ, MacKell S, Gilmour HM. Immunohistochemical assessment of Ki67 and p53 expression assists the diagnosis and grading of ulcerative colitis-related dysplasia. Histopathology. 2000.

- Clausen OP, Rognum TO, Brandtzaeg P. Ki-67: a useful marker for the evaluation of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. J Clin Pathol. 1996.

- Johansson ME, Phillipson M, Petersson J, et al. The inner of the two Muc2 mucin-dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. PNAS. 2008.

- Dorofeyev AE, Vasilenko IV, Rassokhina OA, Kondratiuk RB. Mucosal barrier in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013.

- Di Sabatino A, Ciccocioppo R, Morera R, et al. Role of the epithelium in IBD. World J Gastroenterol. 2012.